474640 Alicanto

| Discovery [1][2] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | A. C. Becker |

| Discovery site | Cerro Tololo |

| Discovery date | 6 November 2004 |

| Designations | |

| (474640) Alicanto | |

Named after | Alicanto [1][2] (Chilean mythology) |

| 2004 VN112 | |

| TNO [3] · detached[4]-ETNO | |

| Orbital characteristics [3][4] | |

| Epoch 17 December 2020 (JD 2459200.5) | |

| Uncertainty parameter 3[3] · 0[1] | |

| Observation arc | 15.94 yr (5,821 d) |

| Aphelion | 608 AU (barycentric)[5] 618.32 AU |

| Perihelion | 47.289 AU |

| 328 AU (barycentric)[5] 332.80 AU | |

| Eccentricity | 0.8579 |

| 5900 yr (barycentric)[5] 6071 yr (2,217,590 d) | |

| 0.6822° | |

| 0° 0m 0.72s / day | |

| Inclination | 25.572° |

| 65.996° | |

| 326.72° | |

| Physical characteristics | |

| 0.04 (est.)[6] | |

| 23.3[10] | |

| 6.5[1][3] | |

474640 Alicanto (provisional designation 2004 VN112) is a detached[4] extreme trans-Neptunian object. It was discovered on 6 November 2004, by American astronomer Andrew C. Becker at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. It never gets closer than 47 AU from the Sun (near the outer edge of the main Kuiper belt) and averages more than 300 AU from the Sun. Its large eccentricity strongly suggests that it was gravitationally scattered onto its current orbit. Because it is, like all detached objects, outside the current gravitational influence of Neptune, how it came to have this orbit cannot yet be explained. It was named after Alicanto, a nocturnal bird in Chilean mythology.

Discovery and orbit

[edit]

Alicanto was discovered by American astronomer A. C. Becker with the ESSENCE supernova survey on 6 November 2004 observing with the 4-meter Blanco Telescope from Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory.[11][1] Precovery images have been found back to September 26, 2000.[3] Alicanto was observed by the Hubble Space Telescope in November 2008, and found not to have any detectable companions.[1] It reached perihelion (closest approach to the Sun) in 2009[3] and is currently 47.7 AU from the Sun.[10] It will be in the constellation of Cetus until 2019. It comes to opposition at the start of November.

With an perihelion greater than 40 AU, Alicanto is an extreme trans-Neptunian object which are practically detached from Neptune's gravitational influence. Its orbit is characterized by high eccentricity (0.850), moderate inclination (25.58°) and a semi-major axis of 316 AU.[1] Upon discovery, it was classified as a trans-Neptunian object. Its orbit is well determined; as of 11 January 2017 its orbital solution is based on 34 observations spanning a data-arc of 5821 days.[3] Alicanto's orbit is similar to that of 2013 RF98, indicating that they may have both been thrown onto the orbit by the same body, or that they may have been the same object (single or binary) at one point.[9][12]

Naming

[edit]On 14 May 2021, the object was named by the Working Group for Small Bodies Nomenclature (WGSBN) after Alicanto from Chilean mythology. The nocturnal bird of the Atacama Desert has wings that shine at night with beautiful, metallic colors.[2]

Physical characteristics

[edit]Alicanto has an absolute magnitude of 6.5 which gives a characteristic diameter of 130 to 300 km for an assumed albedo in the range 0.25–0.05.[7]

Michael Brown's website lists it as a possible dwarf planet with a diameter of 314 kilometres (195 mi) based on an assumed albedo of 0.04.[6] The albedo is expected to be low because the object has a blue (neutral) color.[6] However, if the albedo is higher, the object could easily be half that size.

Alicanto's visible spectrum is very different from that of 90377 Sedna.[9][13] The value of its spectral slope suggests that the surface of this object can have pure methane ices (like in the case of Pluto) and highly processed carbons, including some amorphous silicates.[9] Its spectral slope is similar to that of 2013 RF98.[9]

Relevance to the Planet Nine Hypothesis

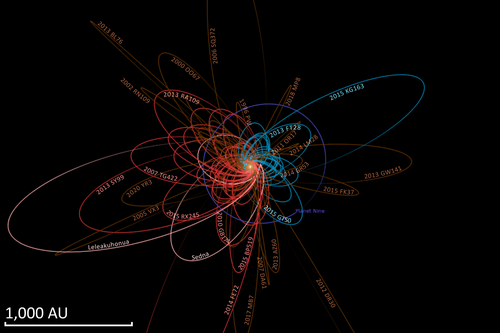

[edit]This minor planet is one of a number of objects discovered in the Solar System to have a semi-major axis > 150 AU, a perihelion beyond Neptune, and an argument of perihelion of 340 ± 55°.[14] Of these, only eight, including Alicanto, have perihelia beyond Neptune's current influence.

Comparison

[edit]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g "(474640) Alicanto". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ a b c "WGSBN Bulletin Archive". Working Group for Small Bodies Nomenclature. 14 May 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2021. (Bulletin #1)

- ^ a b c d e f g h "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 474640 (2004 VN112)" (2016-09-03 last obs.). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ a b c Marc W. Buie (8 November 2007). "Orbit Fit and Astrometric record for 04VN112". SwRI (Space Science Department). Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- ^ a b c Horizons output. "Barycentric Osculating Orbital Elements for 2004 VN112". Retrieved 20 September 2021. (Ephemeris Type:Elements and Center:@0)

- ^ a b c d e Michael E. Brown. "How many dwarf planets are there in the outer solar system? (updates daily)". California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- ^ a b "Asteroid Size Estimator". CNEOS NASA/JPL. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d "LCDB Data for (474640) Alicanto". Asteroid Lightcurve Database (LCDB). Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d e de León, Julia; de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl (May 2017). "Visible spectra of (474640) 2004 VN112-2013 RF98 with OSIRIS at the 10.4 m GTC: evidence for binary dissociation near aphelion among the extreme trans-Neptunian objects". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 467 (1): L66–L70. arXiv:1701.02534. Bibcode:2017MNRAS.467L..66D. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slx003. S2CID 119419889.

- ^ a b "AstDyS 2004 VN112 Ephemerides". Department of Mathematics, University of Pisa, Italy. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ Discovery MPEC

- ^ de la Fuente Marcos, C.; de la Fuente Marcos, R.; Aarseth, S. J. (1 November 2017). "Binary stripping as a plausible origin of correlated pairs of extreme trans-Neptunian objects". Astrophysics and Space Science. 362 (11): 198 (18pp.). arXiv:1709.06813. Bibcode:2017Ap&SS.362..198D. doi:10.1007/s10509-017-3181-1. S2CID 118890903.

- ^ "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 90377 Sedna (2003 VB12)". Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ "JPL Small-Body Database Search Engine: a > 150 (AU) and q > 30 (AU) and data-arc span > 365 (d)". JPL Solar System Dynamics. Retrieved 9 April 2014.